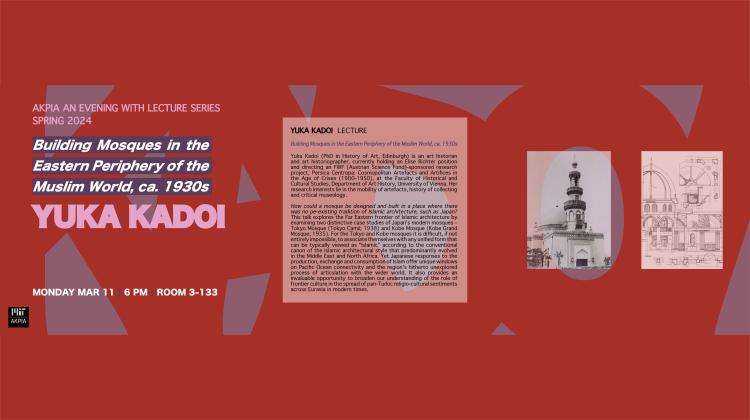

Yuka Kadoi

poster by Ghida Anouti

Yuka Kadoi

Building Mosques in the Eastern Periphery of the Muslim World, ca. 1930s

Yuka Kadoi (PhD in History of Art, Edinburgh) is an art historian and art historiographer, currently holding an Elise Richter position and directing an FWF (Austrian Science Fund)-sponsored research project, Persica Centropa: Cosmopolitan Artefacts and Artifices in the Age of Crises (1900-1950), at the Faculty of Historical and Cultural Studies, Department of Art History, University of Vienna. A native of Tokyo, she acquired a dual background of East Asian Studies (i.e. Japanese Oriental studies) at Kyoto and Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies (i.e. British Oriental studies) at Edinburgh, besides her main expertise in the art, architecture and material culture of pre-modern Eurasia. Her research interests lie in the mobility of artefacts, history of collecting and critical museology. She is the author or editor/co-editor of seven books and three special issues of peer-reviewed journals, including her award-winning Islamic Chinoiserie: The Art of Mongol Iran (EUP, 2009/2018), as well as the author of more than sixty articles in scholarly journals and edited volumes. She is currently finalising the manuscript of her second monograph, The History and Historiography of Persian Art, 1900-1935 (under contract with EUP). She has held fellowships and visiting professorships from the Warburg Institute (London), IASH (Edinburgh), CASVA (Washington, DC), LAU (Beirut), Museum of Ethnology (Osaka) and CEU-IAS (Budapest), while having curated several exhibitions in the past (Chicago [2010], Edinburgh [2014] and Hong Kong [2018]).

Abstract:

How could a mosque be designed and built in a place where there was no pe-existing tradition of Islamic architecture, such as Japan? This talk explores the Far Eastern frontier of Islamic architecture by examining two distinctive case studies of Japan's modern mosques – Tokyo Mosque (Tokyo Camii; 1938) and Kobe Mosque (Kobe Grand Mosque; also known as Kobe Muslim Mosque; 1935). Stylistically different, these buildings reveal the arrival of refugees and expatriates from Muslim-majority countries, especially Tatars, as well as the establishment of their community base in a rapidly modernized and cosmopolitanized insular country. Moreover, they demonstrate the involvement of architects and religious activists from yet another frontier of the Islamic world – namely, Tsarist Russia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Resembling Tatar mosques in Kazan and Astrakhan on one hand and generally vernacular religious structures typical of East Europe on the other hand, the stylistic uniqueness of Islamic architecture in Japan was due to its geographical isolation, surrounded by the sea borders among several distinctive cultures across the Pacific Ocean. For the Tokyo and Kobe mosques it is difficult, if not entirely impossible, to associate themselves with any unified form that can be typically viewed as “Islamic” according to the conventional canon of the Islamic architectural style that predominantly evolved in the Middle East and North Africa. Yet Japanese responses to the production, exchange and consumption of Islam offer unique windows on Pacific Ocean connectivity and the region’s hitherto unexplored process of articulation with the wider world. It also provides an invaluable opportunity to broaden our understanding of the role of frontier culture in the spread of pan-Turkic religio-cultural sentiments across Eurasia in modern times.